Cross Asset Skew - A Trading Strategy

I recently listened to S7E3 of Flirting with Models which had Nick Baltas talking about Multi Asset and Multi-Strategy portfolios. Nick highlighted his work on cross-asset skew and how it can compliment your typical equity factors (momentum, growth, value etc.) and is an under-explored topic in portfolio construction. After reading the original paper, Cross-Asset Skew, I decided to try and replicate the results and see whether skew comes out in the wash and produces any alpha.

Enjoy these types of posts? Then you should sign up for my newsletter.

In this post, I’ll go through what skew is, how it can be used as a trading strategy, and backtest the portfolio across different asset classes. We will then see if it produces any alpha (\(\alpha\)) and or if skew is just market beta (\(\beta\)). I’ll then take a deeper dive into the equity performance and how it compares to the typical factors.

I’ll be working through everything in Julia (1.9) and pulling daily data from AlpacaMarkets.

using AlpacaMarkets, Dates,CSV, DataFrames, DataFramesMeta, RollingFunctions

using Plots, StatsBase

using Distributions

function parse_date(t)

Date(string(split(t, "T")[1]))

end

function clean(df, x)

df = @transform(df, :Date = parse_date.(:t),

:Ticker = x, :NextOpen = [:o[2:end]; NaN], :LogReturn = [NaN; diff(log.(:c))])

@select(df, :Date, :Ticker, :c, :o, :NextOpen, :LogReturn)

end

function load(etf)

df = AlpacaMarkets.stock_bars(etf, "1Day"; startTime = now() - Year(10), limit = 10000, adjustment = "all")[1]

clean(df, etf)

end

What is Skew?

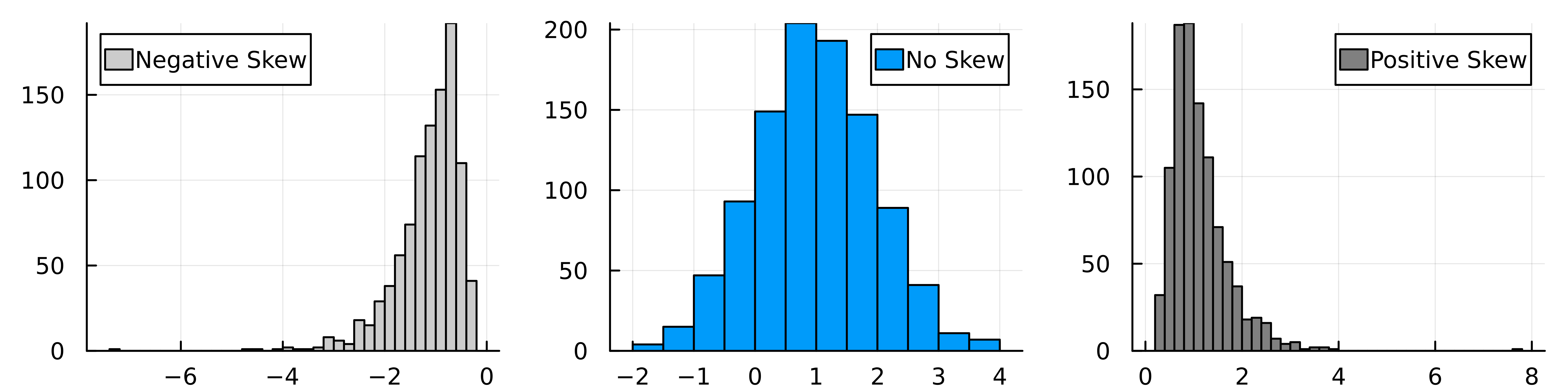

Skew (or skewness) measures how symmetric the distribution is around the mean value. A distribution of values with more values to the right of the mean is a positively skewed distribution and vice versa for the left of the mean.

We can demonstrate this by generating some random values from a skewed distribution (lognormal) and unskewed (normal).

Which shows the general tilt in the x-axis across the 3 different distributions.

Skew is weird in the sense that there isn’t a single way to calculate how skewed a distribution is. For our defined distributions above we can calculate the analytical values of skew and see that it is zero for the middle graph and positive (as expected) for the right-hand graph. Given that we flip the sign of the left-hand graph, that has the negative skew.

skewness.([Normal(1,1), LogNormal(0, 0.5)])

2-element Vector{Float64}:

0.0

1.7501896550697178

In the paper, the skew of an asset is calculated as

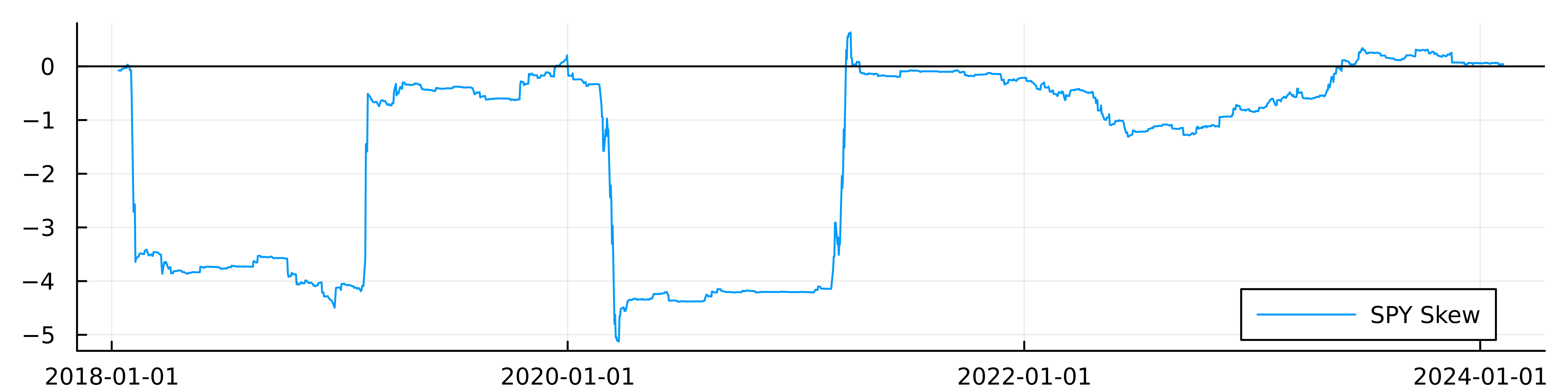

\[S = \frac{1}{N} \sum _{i=1} ^N \frac{(r_i - \mu ) ^3}{\sigma ^3},\]where \(\mu\) is the average and \(\sigma ^2\) is the variance of the returns of an asset with a lookback window of \(N\). We can look at the skewness of the SPY ETF over a 256-day rolling window using the RollingFunctions package.

spy = load("SPY")

spy = @transform(spy, :Avg = runmean(:LogReturn, 256), :Dev = runstd(:LogReturn, 256))

spy = @transform(spy, :SkewDay = ((:LogReturn .- :Avg) ./ :Dev) .^3)

spy = @transform(spy, :Skew = runmean(:SkewDay, 256))

spy = @subset(spy, .!isnan.(:Skew))

plot(spy.Date, spy.Skew, label = "SPY Skew", dpi=900, size=(800, 200))

hline!([0], color="black", label = :none)

It’s jumpy, but the jumps make sense as it’s a \(^3\) calculation, so large values will be amplified. SPY became very negatively skewed over COVID-19 as there were all the market corrections leading to large down days. In recent days it’s now more positively skewed as we’ve seen some larger positive returns.

Skew as a Trading Strategy

The paper believes that skew can predict future returns and that we want to be long assets with a negative skew and short assets with a positive skew. This gives it a ‘mean reversion’ explanation for future returns, so over COVID-19 when there were lots of down days, we should be buying because the movement is likely to be overblown and the market will correct higher. Likewise, large jumps up mean that it’s a positive move that is overblown and will come back down. So again, looking at the skew of SPY in recent weeks, the skew is positive therefore we would be inclined to short this ETF.

The overall strategy is looking at cross-sectional skew, so how skewed an asset its relative to it’s peers rather than looking at the raw skew number on a given day. The paper looks at equity indexes across countries, bond futures across different countries, different currencies, and commodities. In our replication, we are going to be using different ETFs that look at similar themes and should capture the broad cross-section of finance.

The ETF Trading Universe

The original paper uses futures data from 1990 up to 2017 to run the backtest, I will be instead using different ETFs and a much shorter timescale, just because that’s all the data I have available from my AlpacaMarkets free account using AlpacaMarkets.jl.

Blackrock is nice enough to publish this document for their different equity funds across the globe, Around the World with iShares Country ETFs, which I use to get the different country equity performance plus some broader indexes.

For the fixed income part I just try and take a cross-section of the different types of fixed income instruments available and different durations, mixing long-term, short-term, government, corporates, etc.

Commodities, again, just trying to get a broad mix, and the Other class is mainly real-estate and whatever other cruff comes up on the ETF database website. Finally, the currency ETFs each represent a different currency, so cover that part of the paper.

universe = [("Equity", ["SPY", "EWU", "EWJ", "INDA", "EWG", "EWL", "EWP", "EWQ",

"VTI", "FXI", "EWZ", "EWY", "EWA", "EWC", "EWG",

"EWH", "EWI", "EWN", "EWD", "EWT", "EZA", "EWW", "ENOR", "EDEN", "TUR"]),

("FI", ["AGG", "TLT", "LQD", "JNK", "MUB", "MBB", "IAGG", "IGOV", "EMB", "BND", "BNDX", "VCIT", "VCSH", "BSV", "SRLN"]),

("Commodities", ["GLD", "SLV", "GSG", "USO", "PPLT", "UNG", "DBA"]),

("Other", ["IYR", "REET", "USRT", "ICF", "VNQ"]),

("Ccy", ["UUP", "FXY", "FXE", "FXF", "FXB", "FXA", "FXC"])

]

We iterate through all the asset classes and pull the most amount of daily data possible.

allDataRaw = Array{DataFrame}(undef, length(universe))

for (j, (assetClass, etfs)) in enumerate(universe)

println(assetClass)

resdf = Array{DataFrame}(undef, length(etfs))

for (i, etf) in enumerate(etfs)

#println(etf)

df = load(etf)

resdf[i] = df

end

resdfC = vcat(resdf...)

resdfC.AssetClass .= assetClass

allDataRaw[j] = resdfC

end

allData = vcat(allDataRaw...);

We then add in the averages \(\mu\), standard deviation \(\sigma\), and calculate the skew value for that day before taking the rolling average to arrive at the overall skew measure. We need to group by each ETF (the Ticker column).

allData = groupby(allData, :Ticker)

allData = @transform(allData, :Avg = runmean(:LogReturn, 256), :Dev = runstd(:LogReturn, 256))

allData = @transform(allData, :SkewDay = ((:LogReturn .- :Avg) ./ :Dev) .^3)

allData = @transform(allData, :Skew = runmean(:SkewDay, 256))

allData = @subset(allData, .!isnan.(:Skew));

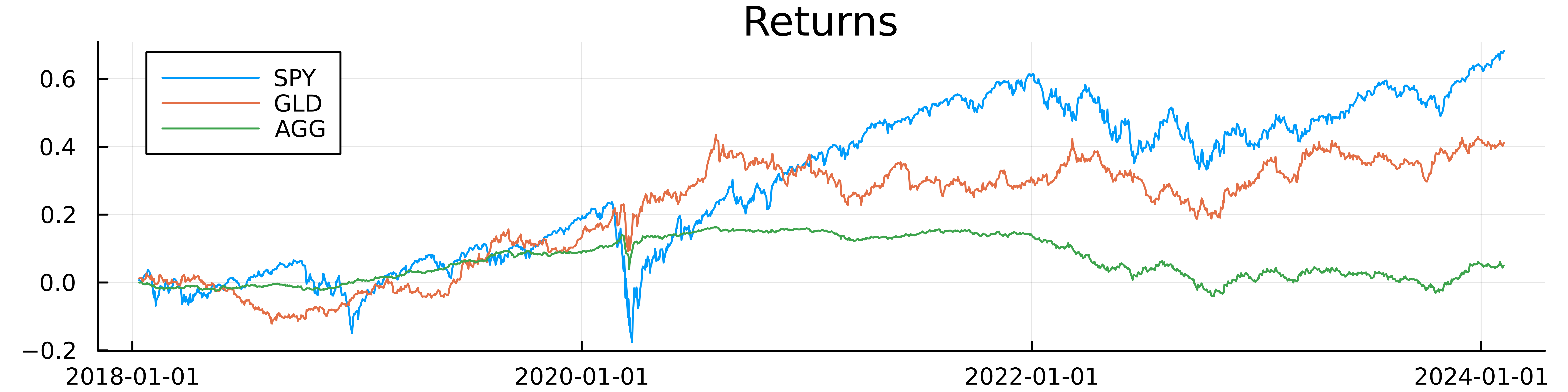

To check we’ve pulled the right data we plot the cumulative log returns.

plot(allData[allData.Ticker .== "SPY", :].Date, cumsum(allData[allData.Ticker .== "SPY", :].LogReturn), label = "SPY",

title="Returns", dpi=900, size=(800, 200))

plot!(allData[allData.Ticker .== "GLD", :].Date, cumsum(allData[allData.Ticker .== "GLD", :].LogReturn), label = "GLD")

plot!(allData[allData.Ticker .== "AGG", :].Date, cumsum(allData[allData.Ticker .== "AGG", :].LogReturn), label = "AGG")

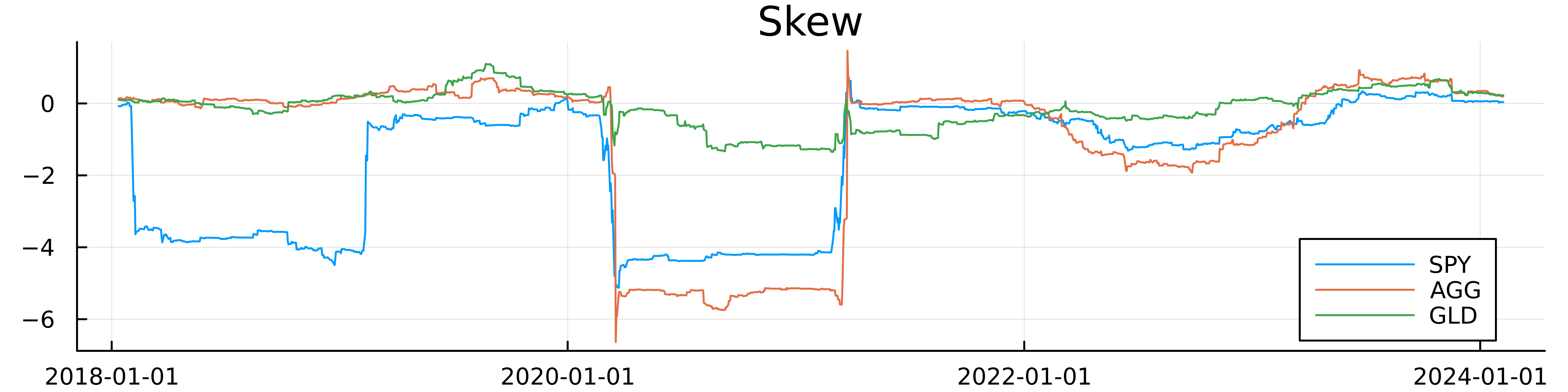

Everything looks as we would expect. We can now look at the skew for these three assets.

The skews move differently and with different magnitudes notably GLD has the least variable skew but equity and bonds have a similar pattern.

The paper looks at the skew of the asset on the last day of the month and uses that to rebalance the portfolio so that with a groupby and last we can pull the skew value on the last day of the month.

Building the Backtest

We need to avoid the look-ahead bias in the backtest. The portfolio weight is calculated using the last day of the month, so we observe the closing price and use that to calculate the return and update the parameters - average return, volatility, and finally the skew. This skew then goes into the weighting calculation but it is only active on the next working day, otherwise, we are getting a ‘free’ day of return.

So on the 31st of the Jan, we update the weights and then do the rebalance on the 1st of Feb (assuming that’s a working day). There is also the additional cost of trading into the position, at the minute we are assuming we can trade at the previous closing price but that is a problem to solve for another day.

allData = @transform(allData, :Month = floor.(:Date, Month(1)), :Week = floor.(:Date, Week(1)));

allData = @transform(groupby(allData, :Ticker), :NextDay = [:Date[2:end]; Date(2015)])

monthlyVals = @combine(groupby(allData, [:Month, :AssetClass, :Ticker]),

:Date = last(:Date), :NextDate = last(:NextDay),

:EOMSkew = last(:Skew));

We rank each asset in its respective asset class using the negative of the skew value, so the most positive skew gets the lowest rank and the most negative skew gets the highest rank. We also normalise the ranks by the number of assets in the group.

To come up with the portfolio weight, we want all the long positions (positive ranks) to have a total weighting of 1 and short positions (negative ranks) to have a total weighting of -1. This corresponds to being long 1 dollar and short 1 dollar so self-financed overall.

monthlyVals = groupby(monthlyVals, [:Date, :AssetClass])

monthlyVals = @transform(monthlyVals, :SkewWeightRaw = ordinalrank(-1*:EOMSkew) .- ((length(:EOMSkew) + 1) /2))

monthlyVals = groupby(monthlyVals, [:Date, :AssetClass])

monthlyVals = @transform(monthlyVals, :SkewWeight = :SkewWeightRaw ./ sum(1:maximum(:SkewWeightRaw)))

For example, if we look at the commodity ETFs and their latest skew values and how that changes the portfolio weights.

| Date | Asset Class | Ticker | EOM Skew | SkewWeightRaw | Skew Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-02-07 | Commodities | GLD | 0.23 | -3 | -0.5 |

| 2024-02-07 | Commodities | SLV | 0.02 | -2 | -0.333 |

| 2024-02-07 | Commodities | DBA | -0.04 | -1 | -0.167 |

| 2024-02-07 | Commodities | PPLT | -0.07 | 0 | 0 |

| 2024-02-07 | Commodities | GSG | -0.12 | 1 | 0.167 |

| 2024-02-07 | Commodities | UNG | -0.16 | 2 | 0.333 |

| 2024-02-07 | Commodities | USO | -0.19 | 3 | 0.5 |

The most negatively skewed ETF, USO, gets the highest positive weight and vice versa. If we look at the weights over the period for the three example assets.

The portfolio weights for both SPY and AGG show that the last two months have been short SPY and no position in AGG. GLD has been allocated in the opposite direction to the other two, right now we are short GLD.

We join the weights to the original dataframe and forward fill the weightings to look at the daily performance. I pulled a forward fill function from https://hongtaoh.com/en/2021/06/27/julia-ffill/ and joining the portfolio weights to the daily returns allows us to understand the daily changes in the portfolios.

ffill(v) = v[accumulate(max, [i*!ismissing(v[i]) for i in 1:length(v)], init=1)]

weightings = @select(monthlyVals, :NextDate, :Ticker, :SkewWeight)

rename!(weightings,:NextDate => :Date)

allDataWeights = leftjoin(allData, weightings, on=[:Date, :Ticker]);

allDataWeights = sort(allDataWeights, :Date)

allDataWeights = @transform(groupby(allDataWeights, :Ticker), :SkewWeight2 = ffill(:SkewWeight));

Plotting the resulting portfolios gives us an idea of their performance.

assetPortfolios = dropmissing(@combine(groupby(allDataWeights, [:Date, :AssetClass]),

:PortfolioReturn = sum(:SkewWeight2 .* :LogReturn),

:MktReturn = mean(:LogReturn)))

p = plot(title = "Skew Portfolios")

for ac in unique(assetPortfolios.AssetClass)

plot!(p, assetPortfolios[assetPortfolios.AssetClass .== ac, :].Date,

cumsum(assetPortfolios[assetPortfolios.AssetClass .== ac, :].PortfolioReturn), label =ac)

end

hline!([0], color = "black", label = :none)

p

These are the results for each asset class. Interestingly, all of them (except Other) have a positive return as of February and most have never fallen below their starting returns. Commodities are very volatile and swung back and forth quite dramatically, equities have been one-way traffic in the right direction!

We also want to combine all the asset classes to produce a single portfolio but first have to normalise the returns by the volatility so that they are equally weighted on a risk basis.

assetPortfolios = @transform(groupby(assetPortfolios, :AssetClass), :Vol = sqrt.(runvar(:PortfolioReturn, 256)))

assetPortfolios = @transform(groupby(assetPortfolios, :AssetClass),

:NormReturn = 0.1*:PortfolioReturn ./ :Vol,

:NormMarketReturn = 0.1*:MktReturn ./ :Vol)

gcf = @combine(groupby(assetPortfolios, :Date), :Return = mean(:NormReturn), :MktReturn = mean(:NormMarketReturn));

plot(gcf.Date[2:end], cumsum(gcf.Return[2:end]), label = "Global Skew Factor", title = "Global Portfolio")

plot!(gcf.Date[2:end], cumsum(gcf.MktReturn[2:end]), label = "Global Market Return")

hline!([0], color = "black", label = :none)

Again, a positive result, well at least recently. This indicates that skew has some associated premium. Now we want to see if this is alpha or beta.

Alpha, Beta or Something Else?

It’s great that these portfolios both at an asset level and global level have ended up in the green but we want to compare the performance to the general market and see if it’s riding the market or adding something new.

This is simple enough to compare, we can look at the equal-weighted return of all the assets in the group and see how that ended up.

Again, all of the skew portfolios have outperformed the market portfolio (except the Other asset class). so this is a good indication that this skew strategy is adding something new.

A more systematic approach is to regress the portfolio return against the market return and this will give us a measure of the \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) of the strategy.

\[\text{Skew Return} = \alpha + \beta \cdot \text{Market Return}\]using GLM

for ac in unique(assetPortfolios.AssetClass)

ols = lm(@formula(PortfolioReturn ~ MktReturn), assetPortfolios[assetPortfolios.AssetClass .== ac, :])

println(ac)

println(coeftable(ols))

println(r2(ols))

end

| Asset Class | \(\alpha\) | \(p\) value | \(\beta\) | \(p\) value | \(R^2\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equity | 0.0003 | 0.0544 | -0.01 | 0.4465 | 0.0003 |

| FI | 0.0001 | 0.1796 | -0.05 | 0.0728 | 0.002 |

| Commodities | 0.0004 | 0.4799 | 0.113 | 0.0232 | 0.003 |

| Other | -0.00004 | 0.5845 | 0.007 | 0.1690 | 0.001 |

| Ccy | 0.0001 | 0.3622 | 0.498 | <1e-27 | 0.08 |

The first thing to note is the low \(R^2\)’s across the board, which is to be expected in these types of models. Generally, the \(\alpha\)’s are all statistically insignificant with only the equity portfolio getting close to significance which indicates that the skew factor isn’t providing ‘new returns’. Interestingly though, only commodities and currencies have a statistically significant \(\beta\) which means for other asset classes the modelling is essentially noise. So whilst the lack of \(\alpha\) is a problem, the lack of \(\beta\) sort of makes up for it. Essentially I think this is a promising sign that there is perhaps something more to be done.

A Deeper Dive With More Equity Factors

An equity fund manager who wants to allocate to skew also needs to verify that skew is providing something unique and not a repackaging of momentum/value/growth/carry factors. This is easy enough as there are ETFs that represent these factors, so we just include it in the regression.

mtum = load("MTUM") #momentum

vtv = load("VTV") #value

vug = load("VUG") #growth

cry = load("VIG") #carry

equityFactors = vcat([mtum, vtv, vug, cry]...);

Joining these with the equity data gives us a bigger dataset to construct the OLS regression.

equity = assetPortfolios[assetPortfolios.AssetClass .== "Equity", :]

equity = leftjoin(equity,

unstack(@select(equityFactors, :Date, :Ticker, :LogReturn), :Date, :Ticker, :LogReturn),

on = "Date")

coeftable(lm(@formula(PortfolioReturn ~ MktReturn + MTUM + VTV + VUG + VIG),

equity))

| Coef. | Std. Error | t | Pr(> \(\mid t \mid\)) | Lower 95% | Upper 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.000280318 | 0.000180867 | 1.55 | 0.1214 | -7.44597e-5 | 0.000635095 |

| MktReturn | -0.300453 | 0.0312806 | -9.61 | <1e-20 | -0.361811 | -0.239094 |

| MTUM | -0.0881885 | 0.0305466 | -2.89 | 0.0039 | -0.148107 | -0.0282701 |

| VTV | 0.450562 | 0.0614928 | 7.33 | <1e-12 | 0.329942 | 0.571183 |

| VUG | 0.109752 | 0.0358138 | 3.06 | 0.0022 | 0.0395015 | 0.180002 |

| VIG | -0.140079 | 0.0739041 | -1.90 | 0.0582 | -0.285045 | 0.00488637 |

Again, no \(\alpha\), significant market \(\beta\), and significant momentum, value, and growth coefficients but no significance with carry. This isn’t great for the Skew factor as this regression suggests we can replicate it using the other factors, namely, it’s anti-correlated to the market and momentum and correlated with value and growth. Given it’s a mean-reversion-esq strategy this makes sense as value is generally about finding underpriced assets.

Conclusion

This has been a successful replication of the original paper, which used ETFs of different asset sectors to explore skew. We now understand that skew is a measure of how left or right-tailed a distribution is, and how it can be exploited in a trading strategy. By calculating skew across different assets and ranking the skew in asset class groups, we allocate long positions to the most negatively skewed assets and short positions to positively skewed assets. This portfolio has produced a positive return in equities, fixed income, currencies, and commodities (but not Other), and has outperformed the market portfolio. A global skew portfolio was also constructed by scaling each asset class to 10% volatility and combining the returns, which also outperformed the market.

The use of the Other asset class was the only sector where skew didn’t work, so it would be hurting the overal skew portfolio, so going forward we would know to restrict the universe to equity, fixed income, currencies and commodities.

However, when we regressed the portfolio return onto the market returns, we found no statistically significant alphas and significant betas. The equity portfolio was close to having a significant alpha, but given it had the largest number of underlying assets, it could be a function of asset size.

We have neglected the trading costs and potential capacity of the overall strategy, but given its low turnover (weights only updating every month), this is probably safe to ignore until you hit the super asset manager size.

Although the results are not as conclusive as the original paper, they are on a shorter timescale and smaller universe, and do not contradict the original findings. We have shown that skew is out there and can provide a source of returns.

Going forward, refining the calculation of the skew and tuning the lookback windows might improve the results. Also, expanding the universe into more specific funds could provide better insights. At the moment, the fixed income component is too broad to pick up on the skew changes.